The Book Designer Who Was Bruce Rogers Part II

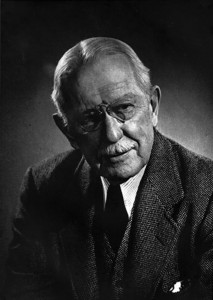

Continuing the chronicle of the activities of Mr. Bruce Rogers, most distinguished of American typographers, whose centenary is celebrated this year, it may be noted that he was frequently referred to in print with the appendage to his name of the respectful “Mr.” But this formality was softened by the universally applied “BR” for a good part of his life.

Continuing the chronicle of the activities of Mr. Bruce Rogers, most distinguished of American typographers, whose centenary is celebrated this year, it may be noted that he was frequently referred to in print with the appendage to his name of the respectful “Mr.” But this formality was softened by the universally applied “BR” for a good part of his life.

Mr. Came Early

As early as 1916, in the first small book to be published about Rogers, the title was Modern Fine Printing in England and Mr. Bruce Rogers. It was written by Alfred W. Pollard, the great bibliographical scholar of the British Museum. During the next 20 years a number of other appreciative papers were published in which the writers referred to their subject as Mr. Bruce Rogers. There is no doubt that the designer’s natural dignity as a human being, tempered by an inherent reserve in his relations with other people, contributed to the respect in which he was held by his biographers.

The Pollard essay dealt primarily with the books which Rogers had designed for the Riverside Press, the printing office of the great Boston publishing firm of Houghton-Mifflin. Pollard was amazed at the versatility of the young designer and remarked “no other printer, since printing began, could point to so varied an output of so high a standard of craftsmanship within so short a time.”

To Riverside

Bruce Rogers’ affiliation with the Riverside Press began in 1896, when he accepted an invitation from George Mifflin, partner in the publishing firm of Houghton-Mifflin to join his staff. In a position which had also been held by Daniel B. Updike, prior to the founding of his own Merrymount Press, Rogers was responsible for a great deal of the production responsibilities associated with a publishing firm.

In 1899 he persuaded Mifflin to establish a fine bookmaking department, to be called Riverside Press Editions. The first volume from (his enterprise was The Sonnets and Madrigals of Michelangelo Buonarroti, completed in 1899. Before Rogers discontinued his association with the firm in 1912. He had designed over one hundred books, establishing himself as a great printer.

Format Experimentation

Since Rogers was allowed considerable latitude in the design and production of the Riverside Press Editions, he made the most of this splendid opportunity for experimentation in the format of the books which were printed at the Press.

From the beginning he individualized his designs, shying away from the dependence upon one or two types, as practiced by the private press printers of the era. Neither did he depend upon the fairly simple concept of producing sets of books, also popular at the time.

Rogers sought out types which had been lying dormant, but which were authoritative cuttings of historic types. He frequently redesigned certain characters which seemed to him to be objectionable, a practice common to his work for the remainder of his life.

The second book from his hand at the Riverside Press, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was composed in types which he discovered at the Press, but which were not being used.

Originally brought from England by Henry O. Houghton, and noted in the Riverside Specimen Book as English Copperface, the types had not seen much use. Rogers renamed the face Brimmer and used it for a number of his books thereafter.

Following the later research of the typographic historian, Stanley Morison, it was discovered that Brimmer was actually the fine transitional type originally cut late in the 18th century by Richard Austin for the English publisher, John Bell. It is now widely admired under the name of Bell.

New Type Face

In his search for types which could give more meaningful expression to his books, Rogers prevailed upon George Mifflin to allow the cutting and casting of a new type for the Riverside books.

As inspiration he used as his source the type of Nicholas Jenson, the 15th century Venetian printer. From Rogers’ drawings, the Worcester punchcutter, John Cummings, made the punches for the new type, which was called Montaigne since it was to be used for the three volume folio edition of Montaigne’s Essays, begun in 1902.

The first use of a trial font of the new type, however, was in A Report of the Last Sea Fight of the Revenge, by Sir Walter Raleigh, which appeared in 1902.

Of the books printed during the Riverside period, one with particular interest to printers is the English translation of Auguste Bernard’s Geofroy Tory. Since the book represents the extraordinary efforts of Rogers to recreate a period, a short account of its type may be in order.

A Caslon was selected and the 14-point lowercase alphabet was combined with 12-point caps. Rogers then altered many of the characters with a graver and trimmed the letters for a closer fit. The font was then rubbed down to add to the “color” and from these revised letters, electrotyped matrices were made for the Monotype machine. .

An interesting comparison to this thick quarto is the tiny, but completely agreeable edition of The Compleat Angler printed in the same year, and using the same type, the Riverside Caslon. Both books attest to Rogers’ ability to seek the essential rightness of design for subject matter which characterizes so much of his work.

Free-Lance Designer

In 1912, by mutual agreement, Bruce Rogers and the Riverside Press parted company, ending an association of fine bookmaking unique in American printing. Rogers went to Europe for rest and study, and upon his return decided to become a free-lance designer.

For the next three years he produced some commercial design and several books, two of which are notable BR items. The first was Franklin and His Press at Passy, produced for the Grolier Club, and the other, printed in association with Carl Purington Rollins in Montague, Mass., was Maurice Guerin’s The Centaur.

Centaur

A small booklet of just eight pages and printed in an edition of 135 copies, The Centaur has become one of the most desirable of all Rogers’ books, since it is set in a new type, adapted from the Montaigne type, and now bearing the name of the book in which it was first used.

For Centaur, Rogers used the same Jenson model, but he had the type enlarged by photography. He then proceeded to draw, with a broad pen, over the original lowercase letters, as rapidly as he could drive the pen. The drawings for the capitals were done more carefully, and the final results were sent to the Chicago punchcutter, Robert Weibking, who used the Pantograph machine for the production of the font.

Several sizes of Centaur capitals were privately cut for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rogers himself kept a 14-pt. font, the only full one cut, for his own use. Finally in 1929 the entire series was cut by the English Monotype.

Of Centaur, Daniel B. Updike wrote, “It appears to me one of the best Roman fonts yet designed in America and, of its kind, the best anywhere.” Most typographers agree with Updike, appreciating his vast authority in the study of printing types.

Next month I hope to complete this tribute to America’s finest designer of books. Undoubtedly numerous libraries throughout the United States will be mounting exhibits of his work. By the time that this account appears, the Grolier Club in New York will have opened its Bruce Rogers exhibition, scheduled for April 15th.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the April 1970 issue of Printing Impressions.